INTERVIEW

A Conversation with Nathan Xavier Osorio

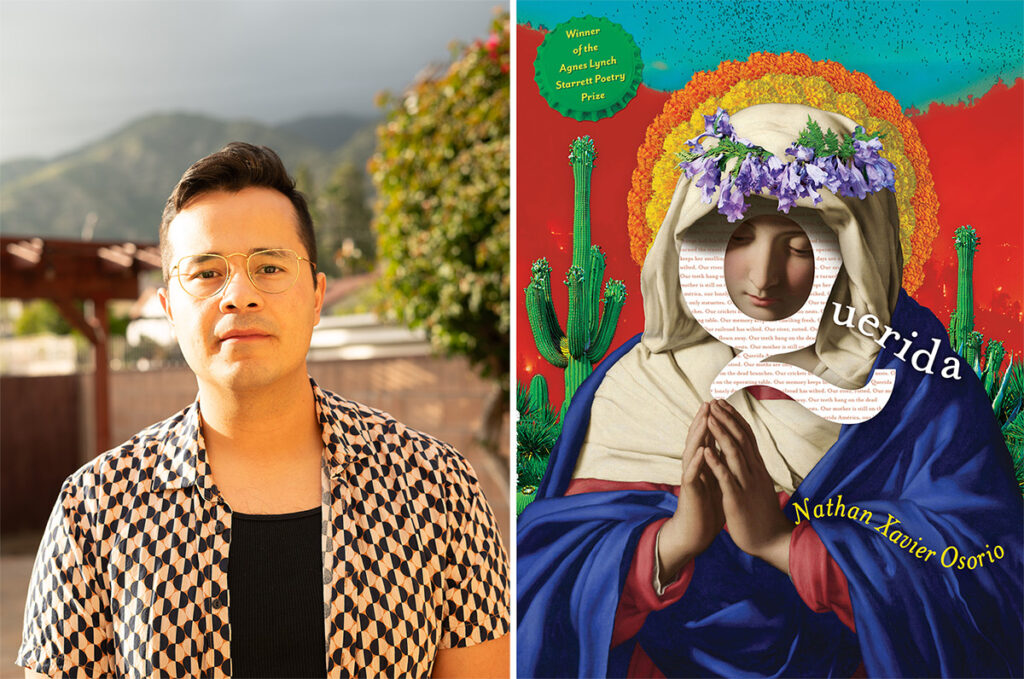

Shō intern Claire Zhou interviews Shō contributor Nathan Xavier Osorio, whose poems “How to Cook a Wolf,” “Empty Stadiums,” and “Come, Little Hunger” appear in Shō No. 4. Nathan’s debut collection of poetry, Querida, won the 2024 Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize, selected by Shara McCallum.

Claire Zhou

Hi! I just wanted to start by asking about your poem “How to Cook a Wolf.” What did you have in mind when you wrote this poem?

Nathan Xavier Osorio

The idea for the poem came to me after reading M.F.K. Fisher’s cross genre survival guide, How to Cook a Wolf (Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1942). It’s a book about cooking in times of crisis, particularly during war and economic recession. I was struck by Fisher’s lyrical prose writing on food and how she reimagined the form of the “cookbook” as a space where we could have a conversation on hunger and survival. By borrowing Fisher’s title I wanted to invoke her grief-ridden idea of having to eat a beautiful animal like a wolf and let it loom in the background. I wanted to sit with that unsettling energy.

Fisher’s cookbook is a tool for sustenance, for feeding people using limited resources and—unfortunately—it still resonates today. I think it serves as a useful parallel for how a poem can operate during ongoing crises. Poetry provides a different kind of nourishment. Writing with Fisher in the background allowed me to enter the poem through a place of longing and intimacy. Be it through poetry or food, nourishing another is such a tender gesture and I think at the core of my poem is a love poem. I get excited about how a poem can enact a type of care, especially as a reaction to our hyperconnected yet ironically fragmented times. I wanted to not only address the figure of the beloved but also try to bring the reader in as close as possible, even to the point of discomfort or strangeness. That kind of horror sensibility is something that interests me as well, especially in this poem. As I was working through drafts, I was thinking a lot about the grotesqueness of luxury in times of hunger, and Cynthia Cruz’s collection The Glimmering Room (Four Way Books, 2012) and Daniel Borzutsky’s The Performance of Being Human (Brooklyn Arts Press, 2016). I think the characters in my poem are navigating a world that is decadent, indifferent, and carnivalesque—capitalism at its ugliest. The allusions to the oceanfront town, the Southern Pacific train, and this exorbitant Kubla Kahn-esque pleasure dome, I hope, build that world for readers.

Claire

That’s very interesting. I think the unsettling nature of the poem does come across, but in a way that also utilizes tenderness. Especially with the first line, “my mother fell in love with the way you cracked into an urchin”—it’s so tender, but it’s so surprising. That’s something I think you really use in your poetry.

I actually had a question for the form you chose to use—is there any particular reason as to why the spacing is done in this way?

Nathan

This poem found its final shape after many revisions. I’m always amazed by how shifts in form in the revision process can affect the way a reader navigates through the poem. I find joy in tinkering around on the page, jumping into and out of formal decisions that sometimes make me feel unsure. Finding the right form is a wrestle that takes time—the missteps are as productive as finally getting it right.

The shape of this poem was inspired by the forms in Eduardo C. Corral’s stellar collection Slow Lighting (Yale University Press, 2012). In it, he builds intimate portraits of family and the beloved using off-set “onelets” interspersed between couplets that are shifting dynamically across the page—but that are also terribly alone. His book was a model for how formal decisions can bring nuance to the character sketches I kept returning to in my work. The mother that appears in this poem and elsewhere in Querida, for example, I imagine as shapeshifting, as present but out of reach. I try to reinforce this for my reader concretely by relying on a teetering and unstable form on the page that can make the frail world in which the poem is set feel more material.

Claire

That makes a lot of sense. You can really see that evolution of the mother, almost—it’s not a static mother character, and it’s something that’s split into two. A multi-faceted approach to a single archetype. Speaking of a mother, how self-reflective do you think this poem is in terms of your own experience with family and survival? Do you think it has any potential as a self-reflective poem?

Nathan

Yes, absolutely! Instances where family or the beloved appear in my work are self-reflective, but it wouldn’t be true to say that they’re representative of a single person or moment of time. Really, they’re more representative of a collage of people, a collage of moments in my life, a collage of reflections across distinct perspectives of a speaker through time. I think there are autobiographical elements in my work—but to return to the idea of the unsettling—I’m most excited when the writing has taken me to a place where the language refuses logic and instead operates on intuition, on sound, on memory. It’s then that I feel like writing can push into worlds that are different from our own but that rely on uncanny archetypes reacting to a world that is surreal but also hyper realistic. These worlds anticipate a future that is built of the conditions that we’re experiencing now. They examine the consequences of decadence, of waste, of the harm that we do to others, to our world, to our environment. In poems like “How to Cook a Wolf,” I’m not interested in parsing these things out. Instead, embedded within the—let’s call it speculation—is both the tenderness and survival, the moments of autobiographical reflection and the reflection on existential threats.

Claire

That’s so cool to hear that this poem has traversed time and space to arrive at where it is now, that it’s made it past all these different versions of yourself to form into this new body of work. Speaking of that, I was wondering about the line that talks about the strawberries from your childhood. It struck me as this almost gentle moment in this carnivorous world—everything is about wolves and snarling and forgiveness, but that line is just so unbelievably gentle. It’s about strawberries and childhood. I was wondering how you manage to input that balance in your work. Do you have a particular way you do it?

Nathan

I appreciate your close-reading and attention to that. I write through revision. In the best-case scenario, I’ll write a poem repeatedly and in a very short and intense period. Throughout those rewritings, it’ll become reshaped over and over again. Once I have the initial seed for the poem I’ll step away for a while so I can come back with a different perspective. I’ll look at the form of the poem and see where it needs balance, see where it maybe goes too far in one direction. I can tell a poem I’ve written isn’t finished when it’s too one dimensional or imbalanced to no effect.

The introduction of the canasta of strawberries at the end of this poem was an attempt to strike a balance—to create contrast in the poem’s concluding moment. I was lucky to take a summer workshop with Natalie Diaz a few years ago now. She introduced the workshop to a strategy for handling a poem that’s swirling around in its own world with many different symbolic elements that are interconnected too loosely. This is an opportunity to create juxtaposition by introducing a very grounding element. It doesn’t have to be overwrought, but just simple and concrete. I’m so glad that you read that strawberry as this gentle counterweight to everything else that came before. I owe Natalie for that wisdom. I think that’s what we see in that final moment—that little fleck of color that pulls us in a different, emotionally provocative direction.

Claire

Definitely. I think especially the bit about color—strawberries being such a vivid red—paints an image, and it’s really startling to read. You’re reading about wolves, and this destruction, and there’s that tenderness, which I think is really well-balanced. It struck me when I first read the poem and upon revision. I’m really happy that it was written—it led me to consider my own work as well. It’s also cool that you had a workshop with Natalie—she’s an incredible poet.

I was also really interested in “Empty Stadiums,” as I’ve never gotten to know the world of baseball. Everything I know is on TV or what I’ve read online, and I’ve never been to a baseball game. Seeing that emptiness, instead of the chaotic nature of a baseball field I’d come to expect, was very unsettling, like you said—that kind of juxtaposition. I was wondering how you came across this idea of an empty stadium, and if baseball has some sort of relevance to your own life.

Nathan

I’m struck by the pageantry of baseball. I’m drawn to its spectacle and promises and the way it’s positioned in our cultural imagination as being nearly natural and entangled with how we experience things like the arrival of spring, the passing of summer, and the inevitable autumn. As a poet and son of immigrants, I find that its mythology and identity as “America’s Pastime” are rich spaces to feel and write through, to critique.

“Empty Stadiums” is about the collapse of a relationship. I was going through a bad breakup and a close friend of mine invited me to his graduation, which was going to be hosted at Angel Stadium. At the time, I was working the midnight shift, so I went to the graduation right after work. The event staff must have felt sorry for me because they let me in early. It was a really emotionally turbulent time of my life, but sitting in the nosebleeds of a stadium with a 45,000 person capacity completely alone stunned me. There was a moment of stillness that felt so alive and in turn made me feel alive for the first time in a while. I sat there and watched the entire transformation of this stadium as it prepared to host the graduates, their families, and the U.S. president who delivered the commencement speech. It was just so bizarre to witness all that life from the vantage point of heartache! There’s that image in the poem where the speaker is trying to hold themselves together with a leather belt because they’ve lost so much weight. In this poem, I was trying to find the grammar of this sensation of depletion alongside the decadence of the baseball stadium and its startling emptiness.

CLAIRE

That’s really interesting. Like you said—a huge event, and you’re literally the first person there. You’re seeing people put up this huge event that is glamorous, but you’re not really part of it. I do think the speaker feels very vulnerable in the entire poem—the speaker is overshadowed by this looming stadium. You captured that moment especially well. It really struck me, especially the line that you pointed out with the leather belt and the screwdriver to be held more in place, because I think other than weight, it also goes to show the way the US produces its clothing. How some of them don’t fit all sizes, how you’ll never feel that you’re really there because it doesn’t fit you. I moved back to China when I was very little, but I do think of how when I went back, I couldn’t even find shoes my size—I had to go to the kids’ section. I just thought that was a very interesting thing. It’s not really about that, but sometimes it feels like it’s about that. “Empty Stadiums,” spoke to me personally.

Nathan

That’s incredible. I’ll set out to write a poem that I’m convinced is a breakup poem, or a poem about baseball, or feeling depressed, but it’s about so much more. Once you’re in the thick of the writing process you realize you’re building a world where other people can insert themselves and find meaningful connections. I think that’s what keeps me returning to poetry, and why I’ve built my life around it. It’s because of this connectivity that it’s able to foster. It’s special.

CLAIRE

Returning to this sense of connection is very interesting to me. English is my second language, and I noticed that you’re very interested in translation and language itself—like syntax, and the way language can almost be a barrier. Do you think that poetry as a medium can speak across language barriers?

Nathan

I think that what poetry can do—which might even be more important than creating bridges—is that it can point out the places where we need them. It can hold our attention and slow us down, so we can begin tending to issues of miscommunication. Reading and writing poetry trains us to act in a more mindful and careful way, inspiring us to attend to our senses and to the possibilities of listening. Poetry’s radical potential lies in how it teaches us to just pay attention.

CLAIRE

Yeah, that’s a really interesting point. There are so few words in poetry as opposed to prose, and you have to be really careful with how you read them. I think it really does teach you that you don’t have to understand everything you’re reading, as long as you get something out of it. You can revisit it always. It makes you almost more delicate in your approach to reading something.

Nathan

That’s a great point. Being okay with not understanding everything can be freeing and open you up to experiences you might have otherwise dismissed. Growing up in a bilingual household where each generation controls a different language made things like going to parent teacher night very interesting. Encounters like that happened across at least two languages and required constant acts of translation and linguistic acrobatics. Losing some meaning in the process of translation was to be expected—and that had to be okay. I learned early on how to live in that space of negative capability.

CLAIRE

Speaking of the experience of being a translator, how do you think that has shaped how you write?

Nathan

Translation helps me do away with the expectation of a one-to-one correlation between one word or another. Bringing an emotion from one linguistic world to another or transforming an emotion within the same language isn’t a mathematical equation. You can’t build linearly towards the sum of an emotion or an image across two languages. Translation helps me instead understand the process of writing as relational and context specific. We experience a page of poetry like a constellation and read through or across it, always looking for connections back to our own lived experiences to better understand the emotion at the center of the work.

The act of translating has also helped me become aware of and see through the illusion of any one language’s claim to superiority. This has been particularly important for me as a writer in the U.S. where we’re so monolingual and have a difficult time seeing past the supremacy of English as the primary language to understand and operate in the world. Literature in translation really troubles that notion and invites us to consider how richly experiences can be conveyed across different languages—languages that have an alphabet, languages that don’t, languages that are informal, that don’t have a name.

CLAIRE

That’s such a valid point to make, especially with parents who struggle to grasp a new language. You said that all languages have their own worth and that they can all communicate meaning in their own way is really vital in the US—which is very predominately English—and in the world as a whole. I think there’s little tolerance for multilingualism—that’s very sad to me. Alternatively, the work you do as a translator is very valuable in making that work possible. I was wondering about your background as the son of immigrants. I’d like to hear some of your thoughts on how it shapes what you write and even your writing process.

Nathan

My parents’ migration to the U.S. from Nicaragua and Mexico and our experiences of living in Los Angeles—a city shaped by generations of immigrant cultures—has shaped how I read and write. These experiences have challenged me to think critically about longing. It’s something I return to, particularly through some of the figures we’ve discussed like the mother or the beloved. I’m interested in the separation between a speaker and the object of their attention and the seemingly impossible act of closing the distance that separates them, of bringing together people or places.

My inheritance as a child of immigrants were the stories I was raised on, stories about homes thousands of miles away, homes entangled with memories and unspeakable traumas. When I’ve been able to visit some of those communities like in Puebla, Mexico, I feel separated from them. My poetry is immersed in a skewed nostalgia that might be the result of being raised in the U.S. but always feeling connected to places that I can’t ever really know. Places that have gone on without me—it’s humbling but disorienting. I’m also interested in this experience as a mark of Americanness, of a U.S. culture that values and is obsessed with its own nostalgia, especially when we think about baseball and its fixation on statistics and record keeping. That nostalgia becomes fraught when we try to imagine the histories and voices lost trying to survive the long shadows of coloniality and capitalism.

CLAIRE

That falsified nostalgia that you’ve only heard about—and you only create this nostalgia because your parents tell you about it—is really interesting. It’s the homeland, but when you go back, it’s like this isn’t my homeland. You can definitely see this come across in your writing—it’s very poignant.

I was wondering if you could describe your debut collection, Querida, in one sentence.

Nathan

That’s a new challenge for me! Let’s see: Querida is a place-based reflection on family and the environments that made me who I am today. I’ll leave it there. That’s what it is in a brief sentence.

CLAIRE

That sounded very professional, so I don’t believe you say you’re new to this. I noticed that rich and evocative imagery generally plays an important role in your work. I was wondering what your policy is on imagery, and how you choose what to put in and what to not put in.

Nathan

In terms of imagery, I’m really inspired by writers like Ross Gay and his collection, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015). In it, he displays a gorgeous obsession with imagery. When I was younger, poets like Walt Whitman and Seamus Heaney also taught me to rely on the image as the core of the poem. My policy—I love that word in this context—is to gather images that will have connections meaningful enough to sustain an initial draft of a poem. That step might happen in a frenzy of writing but once I sober up, my job is to strike the balance I mentioned earlier, but also temper it, make it as manageable as possible so that the unruliness doesn’t overwhelm the sentence. Even in my poetry, the sentence should work as the unit of meaning and allow the grammar to work. This is one way I try to demonstrate courtesy and respect for the reader. They’re giving me their attention, which I think is one of the more precious things we can give another person these days, so I want to make sure I honor that. At the same time, I want to challenge the poetic line and see how far I can push it.

CLAIRE

That’s really cool. What you say about respecting the reader, resonates with my reading of “How to Cook a Wolf.” There was surprising imagery, but I was never really lost. There was the punctuation guiding me, and it wasn’t abrupt—I didn’t feel like it just ended here. Thank you for that, as a reader.

Generally speaking, what is one piece of advice you have for writers? It could be anything.

Nathan

My piece of advice would be to not stop reading. Read as much as you can. Read weird things, read comic books, read things that people wouldn’t imagine a poet would read. Read cookbooks, naturalist guides, sailing manuals, anything that might introduce you to language and grammar with which you’re unfamiliar. Read widely and strangely, and as unruly as you can— and always across languages. If you possess another language, even if just a little, read in that language, even if it makes you uncomfortable. Read literature in translation if that’s more accessible. Read generously and patiently and see what you can gather from others writing across languages, time, and space.

Order Querida by Nathan Xavier Osorio here.

Nathan Xavier Osorio’s debut collection of poetry, Querida, was selected by Shara McCallum as the winner of the 2024 Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize and is forthcoming from the University of Pittsburgh Press. He is the author of The Last Town Before the Mojave, selected by Oliver De la Paz as a recipient for the Poetry Society of America’s 2021 Chapbook Fellowship. He received his PhD in Literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz. His writing has also appeared in BOMB, The Offing, Boston Review, Public Books, and the New Museum of Contemporary Art. His writing and teaching have been supported by fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center, The Kenyon Review, and Poetry Foundation. He is a Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellow at UC Irvine.

Claire Zhou is a student currently residing in Suzhou, China. Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Chestnut Review, DIALOGIST, Notre Dame Review, Moon City Review, Gulf Coast, and Shō Poetry Journal. She loves baking.