INTERVIEW

What’s Possible When Poetry Is Direct

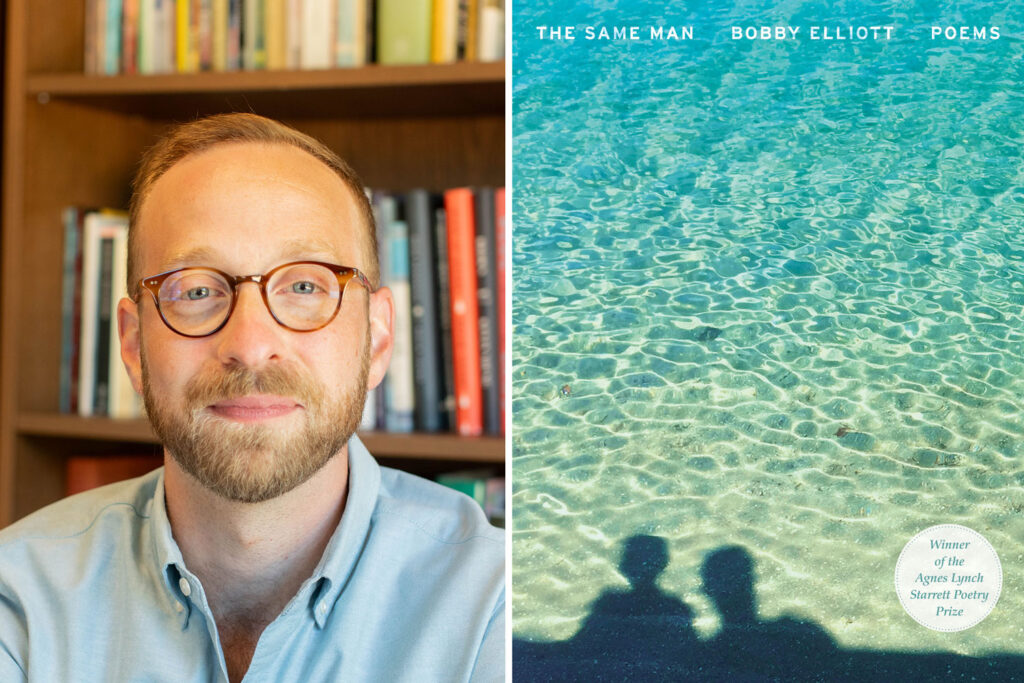

Bobby Elliott on The Same Man (University of Pittsburg Press, 2025)

Shō No. 6 contributor Nicholas Pierce interviews Shō No. 7 contributor Bobby Elliott on his debut full-length poetry collection The Same Man, winner of the 2025 Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize, selected by Nate Marshall.

NICHOLAS PIERCE

In “Mondegreen,” the book’s powerful opening poem, an overheard sound causes the speaker to imagine a tragic scenario: “my father stumbling / into the light of the backyard / / to shoot himself.” On my first read, I thought that the poem was recounting a memory of an event that had actually happened, when in fact—as we learn later in the collection—the father has not taken his own life despite his many threats to do so. The confusion is obviously intentional (the poem’s title, after all, refers to the new meanings that emerge out of the mishearing of a song lyric), so I would be curious to hear you speak about the decision to begin the book in this way.

BOBBY ELLIOTT

It’s a great question, Nick – and one I haven’t been asked yet, so I’m excited to talk more about it here.

On the most fundamental level, I wanted the reader to immediately inhabit the mind of someone who’s in constant fear of losing a parent to suicide. It is the air the collection breathes – and the air I breathed for so long. But it felt equally important to have the reader enter into the book on the precipice of something else entirely: the birth of our son.

My hope is that “Mondegreen” achieves that – and helps set the stage for the poems that come, which are, of course, poems that grapple with the specter of death and the radical emergence of life. And I was comfortable with a reader wondering – as you did – if the father had already died, in the same way that I was comfortable ending the first section of The Same Man with “Prodromal,” a birthing poem that exists in a place of agonizing waiting and anticipation, as opposed to birth itself. I didn’t want to create confusion exactly, but I did want to create the kind of deep-seated uncertainty that I endured in those moments. And I felt confident that the poems to come would answer any lingering questions that truly needed answering.

NICHOLAS

There is an aesthetic consistency to the poems of The Same Man, many employing short lines, couplets, and direct speech—and achieving a searing clarity in the process. This would be remarkable for any collection, but it is especially impressive for a debut. Can you please discuss how you landed on this shape and style for the poems—why, that is, it was the appropriate vessel for the story you were telling?

BOBBY

When I first started reading poetry as a teenager, I knew that I loved it but I also knew that I had no idea what the vast majority of it was communicating or saying. That didn’t stop me from falling more deeply in love with poetry as time went on, but it did push me to seek out poets whose work felt absolutely vivid and within reach. At first, it was Langston Hughes who stole the show, but I eventually found so many poets writing in this mode, from Philip Levine and Lucille Clifton to Edgar Kunz and Natasha Trethewey. With The Same Man, I’ve tried to join them and at least aspire towards a searing level of clarity.

Matt Nienow, an incredible poet and friend of mine, talks often about how having a book in the world means that you’re entering into the greater, never-ending conversation of the art form itself. And that’s helped me think about this book as an attempt to ask what’s possible when poetry is direct, when it is vivid, when it is clear and when it is, yes, accessible. I don’t think of accessibility as a dirty word at all; I think of it as a defining characteristic of the work I love most, which is, of course, also complex and nuanced, serious and realized.

When it comes to form, I often think of it as a gateway. How do the shapes of poems allow, or prevent, a reader to engage with them? How can we actively work towards forms and shapes that aid a reader’s ability to more fully engage with the work itself? My hope is that the consistency you mentioned, and even the design of the book itself, is a step towards that ambition or goal. And while there are plenty of fun, dynamic and meaningful ways to spice things up within a collection, that’s not what this book warranted. This book needed to be unbothered by trends – at least on some level – and just get on with the work it needed to do, pyrotechnics be damned.

NICHOLAS

“New Parents” is about new life, but it opens with the speaker and his wife contemplating their own deaths: “As soon as you’re born, we picture ourselves / dying…” This got me thinking about how parenthood and mortality are inextricably linked in the collection, with the father’s threats of suicide hanging over the speaker from a very early age. I wonder if becoming a father yourself changed your conception of your own lifespan, and of time more broadly, and if so, how those feelings worked their way into the collection.

BOBBY

It did, Nick. And I think what it is, ultimately, is that you are suddenly holding another human being whose life you would do absolutely anything to protect. And that poem, “New Parents,” enacts this sense of responsibility and fantasizes – as we did – about risking, or ending, our own lives to achieve it. As desperate as I am to live as long a life as I possibly can, there is no question in my mind that the lives of our sons matter so much more than ours. And we both felt that way from the minute they were born.

The conundrum (or one of them at least) is that this fantasy will almost certainly never come true – we can’t actually protect our children in the ways we long to, we can’t step between them and whatever danger inevitably awaits. And you read a book like Gabriel by Edward Hirsch and you realize that in the most excruciating way. But something else that’s always on my mind is setting out to provide testimony – a record, a chronicle – of the unique blessing it is to be a parent at all. For as hard as it is, parenting is so profoundly enriching and I’ve tried to write poems – while I’m alive – that give voice to this. That make someone else know what a privilege it’s been to spend these years looking after these two incredible boys.

NICHOLAS

The Same Man follows a roughly chronological structure, beginning with the speaker’s difficult childhood and moving on to his more joyous experience as a husband and father. What most impressed me, however, was how the poems build on each other, returning to certain themes (water and drowning, for example, come up several times) and charting the evolution of certain figures and relationships (most acutely, that of the speaker and his father). Can you talk about the building of this collection? Did you always intend for the poems to exist in this order, with clearly delineated sections, or were there versions of the book that leaped back and forth between the various timelines?

BOBBY

Early on, a few people who read drafts of The Same Man noted how much it had in common with memoir and while that wasn’t something I set out to achieve, I understand it. There’s some aspect of me – and sometimes I have to resist this – that longs to chronicle what happened on the most basic and human level. And naturally, I think that shows up in the way I’ve gone about structuring this book, which does, as you say, follow a roughly chronological structure.

I like that about it – and think it’s allowed people, including those who don’t typically read poetry, to enter into the book and feel like they can move through it – but I also didn’t want it to feel stale or strictly chronological. So, there’s a fair amount of movement between the past and present (and back again) throughout, especially in the second section, that I hope keeps it feeling alive and dynamic – and imbued with this sense that the present is always a portal to the past.

Finding the three-part structure for The Same Man took time. I did all the typical things, printing everything out and moving poems around on the floor of my writing room, and I read aloud just about every iteration of the manuscript to evaluate the movement and flow of the whole. Poems were cast aside as a result (including poems I liked) and I think I even experimented with no section breaks at all. Ultimately, the three-part structure was the right one for the book – and once I found it, The Same Man clicked into place.

But to your point, the poems themselves build on each other and about midway through the process of writing them, I had a sense of what I was writing into, of the kind of book I was after. So, when it came time to plot out the book, the poems had already done much of the work. Not all of it, of course, but a lot of it – they were just waiting for me to figure out where they all fit.

NICHOLAS

In its juxtaposition of the speaker’s experience as a son with his experience as a father, the book raises questions of inheritance: how do we escape the influence of our parents, or can we? what do we take from them and what do we reject? I’m interested in hearing what you learned about yourself, both as a son and a father, from the writing of these poems. I’m interested, too, in hearing about your artistic influences. Which poets helped you to write The Same Man? Are there any collections in particular that you were drawing from?

BOBBY

What did I learn about myself as a son and a father in writing these poems? As a son, I learned that I had a desperate need to be heard – stemming from a childhood and adolescence shaped by my silence – and I learned that I was willing to live with the consequences of writing a book like this if it meant that I could finally speak. As a father, I learned that my journey as a parent would never be separate from my journey as a son – regardless of how hard I’ve tried to free myself of the past. Or how naively I once thought of what it would be like to be “my own person.”

The poems taught me this, again and again, both in insisting on being written and in leading me back to the well of memory.

In terms of the poets who helped me write The Same Man, the list is long, of course, but I was on a huge Kevin Young kick as I wrote these poems – so huge that I had to actively steer clear of him for a bit to regain my own syntax!

I also kept returning to a constellation of poets and collections that reminded me of what I hoped to do: Edgar Kunz’s Tap Out and Fixer; Hafizah Geter’s Un-American; Cornelius Eady’s You Don’t Miss Your Water; Matthew Dickman’s Husbandry; Michael Dhyne’s Afterlife; Geffrey Davis’ first three books; everything Natasha Trethewey has written; everything Marie Howe has written; Martín Espada’s Floaters; Keetje Kuipers’s All Its Charms; James Davis May’s Unusually Grand Ideas; Chloe Honum’s Lantern Room; Ross Gay’s Be Holding (one of my very favorite long poems); Patrick Phillips’ Song of the Closing Doors; and – always – Philip Levine and Lucille Clifton.

Obviously, not all of these deal with the subjects of The Same Man, but they were – and remain – north stars.

Order The Same Man by Bobby Elliott here.

Bobby Elliott’s debut collection, The Same Man, was selected by Nate Marshall as the winner of the 2025 Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize and was published this month by the University of Pittsburgh Press. His writing has appeared in or is forthcoming from BOMB, The Cortland Review, ONLY POEMS, Poet Lore, Poetry Northwest, RHINO, and elsewhere. He lives in Portland, Oregon with his wife and sons.

Nicholas Pierce is the author of In Transit (Criterion Books, 2021), winner of the New Criterion Poetry Prize. His poems have appeared on Best American Poetry’s website and in such journals as 32 Poems, AGNI, The Hopkins Review, Image, Literary Matters, Revel, and Subtropics. He is completing a Ph.D. in Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Utah, where his honors include the University Teaching Assistantship, the Sherman B. Neff Fellowship, and the Jeff Metcalf Fellowship in the Humanities.

This interview was published on September 29, 2025