To celebrate Native American Heritage Month, we’ve curated this selection of poems by Indigenous U.S. poets Danielle Shandiin Emerson (Diné), Chris Hoshnic (Diné), Malia Maxwell (Kanaka Maoli), Tim Moder (Chippewa), Sofia Rasic (Cherokee), and J.K. Tsosie (Diné). Their work was recently published in Shō No. 7 and Shō No. 6.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

- “Grouse Season” by Malia Maxwell

- “Ambedo” by Sofia Rasic

- “THE TRUE PARADISES ARE THE PARADISES WE HAVE LOST” and “LEST WE FORGET THAT NATURE IS NOT OUR FRIEND” by J.K. Tsosie

- “Pawnshop nikon eulogy” by Danielle Shandiin Emerson

- “Evel Knievel in My Grandma’s House” by Tim Moder

- “Event / Response” by Chris Hoshnic

“Grouse Season” by Malia Maxwell

Grouse Season

Rich as the lake, a widow inverts

two moose skulls onto pink fleece.

Their antlers crest from one side

of her bed to the other, suspending

jaws like moons. She’ll brush their teeth

with white vinegar in the next month.

For now, she paints them—darlings—

with bitter principles, teaching dogs

where not to chew. There is no meat.

In the Bone House, dogs hunt

what shadows drip through windows

and bank in tandem with the snow.

Soon, dark rises knee-high in every

room. The widow tends it like a child

and sends her brother into winter,

off to shoot hat bands from spruces.

Their forest is a gown to land and lake.

Water makes two of everything—

mountains clad in ice—yellowed larches—

even wind-burned faces. In the cold,

death ripens for her. She plans

for enough feathers to make a cape.

About this poem: In ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, “ka wai” means “water,” and “ka waiwai” means “wealth.”

“Grouse Season” appeared in Shō No. 7.

Malia Maxwell (Kanaka Maoli) is a writer from Seattle, Washington. Her poems appear or are forthcoming in The Kenyon Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, Black Warrior Review, and elsewhere. Her writing has been supported by scholarships and fellowships from Bread Loaf Environmental and the Vermont Studio Center. She holds an MFA in Poetry from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program. Visit her at maliamaxwell.com.

“Ambedo” by Sofia Rasic

There’s a pillow on my father’s dashboard that holds a pine grove inside. It smells of sap broken in the breeze, borne of firs damp with melting snow. I knew a forest like that once, but I think it was cut down for lumber & I cried because it didn’t have a name to be remembered by. We drive past the farms, fields golden with wheat and dying sunlight. The reeds fall away from the wind though they thought they were stronger. The future lies mysterious & far beyond, cloaked in a silver fog / creeping forward. Like when you can smell the petrichor but the clouds are indecisive. They trudge ahead in the open sky as fat elephants do, wandering aimlessly until the atmosphere swallows them.

About this poem: I don’t think there was one specific moment that inspired this piece. I wrote “Ambedo” in my boarding school dorm room, completely homesick and reminiscing about my childhood in the Hudson Valley. After being away from home for so long, even the smallest change feels disorienting, because in your mind, your hometown stays exactly as you left it. This poem is my attempt to put words to that distance– to the hesitancy to cope with change and the ache of realizing that nothing, not even home, stays the same.

“Ambedo” appeared in Shō No. 7.

Sofia Rasic is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation based in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, but hails from the Hudson Valley, New York, and attends school in northwest Connecticut. Though she finds small pieces of herself scattered across many miles, she always returns to creative writing to feel grounded. “Ambedo” is her first published work.

“THE TRUE PARADISES ARE THE PARADISES WE HAVE LOST” and “LEST WE FORGET THAT NATURE IS NOT OUR FRIEND” by J.K. Tsosie

THE TRUE PARADISES ARE THE PARADISES WE HAVE LOST

My father rarely talks about his life—even to this day, he stays mum as ever. Like a night blooming cereus, he blossoms sporadically and preciously, telling me a story every now and then. Like how he discovered an Anasazi plate at the Mesa Verde Museum featuring a plant with variously colored flowers. His brother, my uncle, committed suicide way back before I was born. He had epilepsy, likely from a head injury he sustained during childhood. It is said that he fell and hit his head against a cement cinder block when he was about 5 years old. His father, my grandfather, was laying down the foundation for their new home. By the time he was nineteen, he felt deeply ashamed of his epilepsy, his episodes getting progressively worse. So, he drove my father’s truck deep into the pińoned landscape and shot himself in the head. It is hypothesized that dogs instinctively want to die alone because their body will attract predators, endangering the rest of the pack. The community searched for days looking for him, gravely discovering his body almost a week later. My father was told by a traditional Diné healer that a plant with flowers, each a different color, like the one he found painted on a 700-year-old Anasazi plate, would hold the cure to his brother’s seizures. To this day, he continues his quest to find this miraculous plant species—I figure he holds himself responsible for his brother’s death having never found it in time. Over the years, I have managed to piece these scant details together, as I would imagine astrophysicists at NASA piece together the biography of our universe.

About This Poem: The title is a quote from Proust — written in French, there have been disagreements over its English translation, but I consider this the most correct. The poem was originally part of an essay I was writing about war and how I did not really understand my father until I joined the military in an attempt to follow in his footsteps. Like most queer men, my relationship with my father has been at times, very contentious. As his only son, I never really lived up to his expectations of traditional masculinity. Similarly to the Proust quote, I found myself living in the past, always trying to live up to this imagined obligation. In the end, I found this section tangential to the essay and decided to make it a stand-alone poem. I never really tried to know my parents until adulthood — this poem is about how much we have learned about each other in the past few years. When I was asked to record this poem, I wanted to layer in the sound of Saturn’s rings into the background — I was drawn to this idea of my father as the vast universe and myself as a mere satellite.*

*As an engineer/scientist, I was immediately in awe when NASA released the sounds of Saturn’s rings — there is an eerie aura about it, a palpable isolation. Of course, I wanted to know how the sound was captured given that there is no air in space. NASA was able to achieve this by converting electromagnetic waves, basically light, into audible frequencies.

from LEST WE FORGET THAT NATURE IS NOT OUR FRIEND

it is the beginning

of summer & the rain still

has not arrived

so, we gather

in the mouth of an arroyo

Click here to read the full poem “LEST WE FORGET THAT NATURE IS NOT OUR FRIEND” by J.K. Tsosie (PDF opens in new tab)

About this poem: The title was inspired by YouTuber Kimberly Foster, who said — “let us not forget that nature is not our friend.” She was talking about how there had been an increase in work call-offs due to extreme heat, particularly in the Phoenix metro area that gravely affected the US GDP. The poem itself is a response to Native parody videos about our relationship with nature — I get that they’re meant to be funny, but self-deprecation is a slippery slope. I was always taught that nature was never our kin, it was never our equal. It has always reigned above us. Thus, the poem is a prayer of sorts. It begins by describing the Navajo ceremony done for rain during drought that I was taught by my parents and precedes into the translation of the song sung during that ceremony in the second part of the poem. The third part of the poem is about excess, about pushing nature to the other extreme — which is where I think were are with the current climate crisis. The last part of the poem is another translation, this time of a Protection Way song that I really thought highlighted the hostility of nature, and how that could be harnessed to defend oneself. In that sense, nature is like a parent teaching us survival skills. This poem and similar ones I have written have been about sharing what my parents and grandparents taught me — I have been fortunate to have been raised the traditional way. They are a means of cultural preservation.

“THE TRUE PARADISES ARE THE PARADISES WE HAVE LOST” and “LEST WE FORGET THAT NATURE IS NOT OUR FRIEND” appeared in Shō No. 7.

J.K. Tsosie is a member of the Navajo Nation — Bitterwater Clan, born for the Many Goats Clan. His work has appeared in Shō Poetry Journal, the Yellow Medicine Review, and the Indiana Review. He is a recipient of the Oberon Herbert Prize, the James Hearst Poetry Prize, and the James Welch Prize for Indigenous Poets. He resides in Albuquerque, New Mexico (Tiwa Territory) where he is completing an MD/PhD at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine.

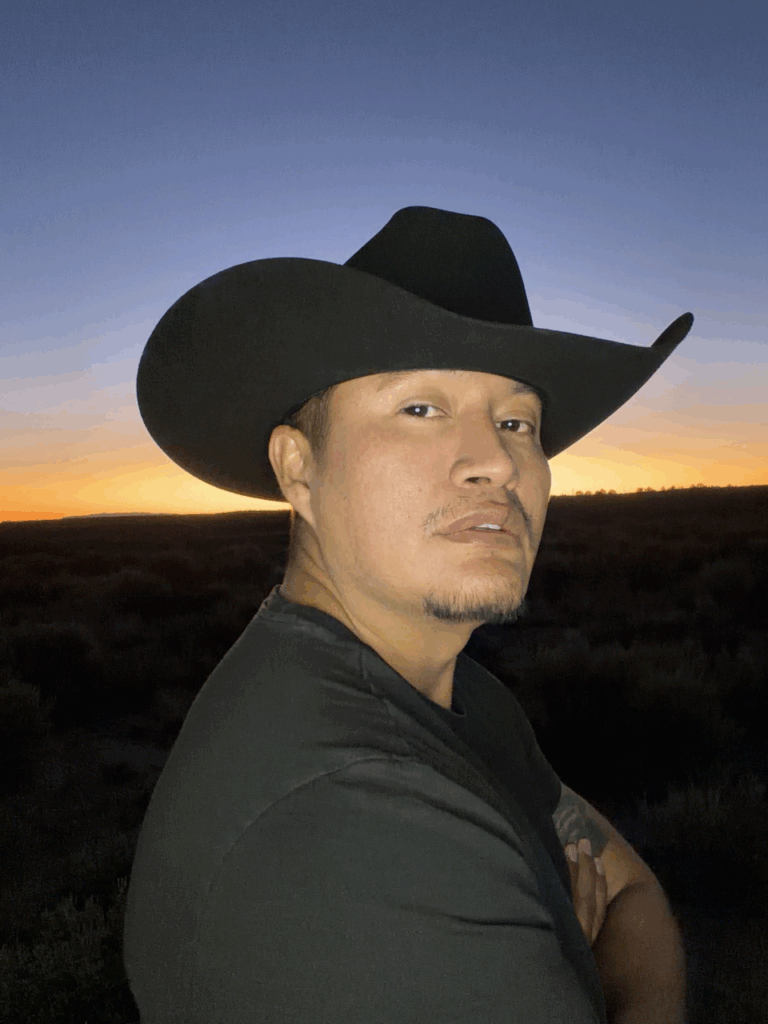

“Pawnshop nikon eulogy” by Danielle Shandiin Emerson

About this poem: I spend a lot of time looking through old photographs. Especially after losing my father. He was a complicated man. And I’m still working on forgiving him. But I like to think I captured the good side of him in that obituary photo, which doesn’t contain all of the truth of who he was, but at least captured what I want to remember. A funny anecdote about this poem, me and my youngest sister argue about who actually took our father’s photo, since I let her play with my camera pretty often. I have a vivid memory of taking the photo, but so does she. It doesn’t really matter, but just in case she’s reading this, I’ll give her photo credit (just in case she’s actually right and I’m wrong).

“Pawnshop nikon eulogy” appeared in Shō No. 7.

Danielle Shandiin Emerson is a Diné writer from Shiprock, New Mexico on the Navajo Nation. Her clans are Tłaashchi’i (Red Cheek People Clan), born for Ta’neezaahníí (Tangled People Clan). Her maternal grandfather is Ashííhí (Salt People Clan) and her paternal grandfather is Táchii’nii (Red Running into the Water People Clan). She has a B.A. in Education Studies and a B.A. in Literary Arts from Brown University. She has received fellowships from GrubStreet, Lambda Literary, The Diné Artisan + Author Capacity Building Institute, Ucross Foundation, Vermont Studio Center, Tin House, The Highlight Foundation, and Monson Arts. She has work published from swamp pink, Academy of American Poets, Yellow Medicine Review, POETRY, Thin Air Magazine, The Chapter House Journal, Poetry Northwest, and others. She is currently a MFA Fiction graduate student at Vanderbilt University.

“Evel Knievel in My Grandma’s House” by Tim Moder

Evel Knievel in My Grandma’s House

I wake up walking through my grandma’s kitchen in the dead of night. I open the refrigerator. It is empty. I hear the teapot whistle from the stove behind me. I turn to see Evel Knievel, his body in a cast. He asks me to power him up. I pour him some tea. I tell him, “I liked your jump over the Grand Canyon.” He says, “It was the Snake River not the Grand Canyon.” A bulging blue rattlesnake crawls from my grandma’s bread box. I turn to see Evel taking some bandages from a shelf. He is standing in aisle three at Walgreens. The one they built on the site that was my grandma’s house. I sit down in my grandpa’s chair. The one I used to get in trouble for sitting in. I close my eyes and spin, knocking over a rack of sunglasses. Evel whistles. He says, “Let’s get some food into that refrigerator. I’ve never seen a fridge so empty.” I turn to see the photo counter decorated with pictures of other people’s families.

About this poem: The poem, “Evel Knievel in My Grandma’s House” was written from a prompt in a Jose Hernandez Diaz workshop on Surrealist poetry. I was living out of town when my grandma sold her house to Walgreens. I remember the first time I sat in the parking lot and looked at the store seeing where my grandma’s house had been. It was as if being in two places at once. I’m in the store frequently and I still feel my “Place” as I’m walking through. As kids, my uncle and I used to play with Evel Knievel action figures. He was always beat up and broken. I was surprised to find him making an appearance in this poem but I guess I was feeling kind of beat up and broken myself. It felt good to write and all my aunts and uncles had a little time-travel while reading it.

“Evel Knievel in My Grandma’s House” appeared in Shō No. 7

Tim Moder is a poet from northern Wisconsin. He is an enrolled member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. He lives with his cats in a house that is too big. His poems have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Cutthroat, South Florida Poetry Journal, Glassworks, and others. He is the author of the chapbook, All True Heavens, The Angel of Coincidence, and American Parade Routes.

“Event / Response” by Chris Hoshnic

from Event / Response

we do not only talk about Trauma

but see it as a physical being resting

somewhere in our bodies

Click here to read the full poem “Event/Response” by Chris Hoshnic (PDF opens in new tab)

“Event / Response” appeared in Shō No. 6.

Chris Hoshnic is a Navajo Poet, Playwright, and Filmmaker from Sweetwater, Arizona. A recipient of the Poetry Northwest 2025 James Welch Prize, Hoshnic’s work has received support from Indigenous Nations Poets, Playwrights Realm, Tin House, Juniper Institute, and more. His work has been published in POETRY, Kenyon Review, and elsewhere. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Chapter House Journal, an online indigenous-centered literary magazine. Hoshnic currently directs Diné Kids Film Club, an Indigenous youth project dedicated to giving resources and networking opportunities for young Native filmmakers. He is also currently an MFA candidate at the Institute of American Indian Arts.